How Jason Web Tokens Work

From jwt.io itself: “JSON Web Token (JWT) is an open standard (RFC 7519) that defines a compact and self-contained way for securely transmitting information between parties as a JSON object. This information can be verified and trusted because it is digitally signed. JWTs can be signed using a secret (with the HMAC algorithm) or a public/private key pair using RSA or ECDSA”.

Let’s unpack that.

Why JWTs are Useful

The main use case for JSON Web Tokens is user authentication. You get a JWT when you log in to a server and use it in the headers of subsequent requests. You can include information like access levels and permissions, for example. Servers that trust the authority that generated the JWT confirm it was issued by them using a shared secret or public key, and can then trust the data within that JWT without querying a validation API. This makes queries more asynchronous, performant, and decentralized.

It is usually sent using the Bearer scheme in the header, like this:

Authorization: Bearer token

This is especially useful in application scalability and Single Sign-On (SSO) scenarios. In a multi-instance application scenario, the less state you need to maintain, the better. It causes fewer cache validation/invalidation issues. If you need to query a database to validate whether a user is valid or not, every request ends up generating a query. This creates more traffic and higher database usage, which isn’t desirable, especially in application layer redundancy scenarios.

In SSO scenarios, they are also interesting because you have a central entity that validates who the users are, while various other services don’t need to do this work again. Other services can trust, via the digital signature, that the user has those access rights.

The Structure of a JSON Web Token

As the name implies, JWTs are composed of 2 JSON objects: the header and the payload, transformed into base64Url, plus the hash. These 3 items are concatenated with dots.

The header typically consists of the token type and the signing algorithm used. For example:

{

"alg": "HS256",

"typ": "JWT"

}The payload usually contains the claims, which are statements the owner makes through the token. There are 3 types of claims:

- Registered: These are predefined by the specification. They aren’t mandatory but are recommended to provide a set of useful, interoperable information between systems using JWT. Examples include iss (issuer), exp (expiration). This list can be found in RFC 7519;

- Public: These can be defined arbitrarily, intended for use by all systems using this token. To avoid collisions and maintain standardization, a standard list defined here is followed: registered, public, and private claims. Alternatively, a unique URI (site name) can be used to prevent collisions.

- Private: These are customized and created to share information between private parties that agree on their use, fitting neither the registered nor public categories.

As a fictional example, below is a JSON with 6 registered, 3 public, and 3 private claims in sequence:

{

"iss": "https://auth.example.com",

"sub": "user_12345",

"aud": "https://api.example.com/v2",

"exp": 1735732800,

"iat": 1735729200,

"jti": "887321-4422-9912",

"email": "jane.doe@enterprise.com",

"locale": "en-US",

"https://example.com/jwt_claims/subscription": "gold",

"tenant_id": "tenant_9901",

"app_roles": ["admin", "editor"],

"feature_flags": {

"beta_access": true,

"dark_mode": false

}

}Keep in mind:

{{< callout type=“warning” >}} All information present in a JWT is public {{< /callout >}}

All information in a JWT is not encrypted and can be read by anyone. Its signature serves to audit that it was signed by who claims to have signed it, but it doesn’t hide the information. For confidential information, values must be encrypted within the JSON, or depending on the case, JWE (JSON Web Encryption) should be used.

Think of JWTs as digitally signed documents where anyone can read the content. The accompanying signature serves to validate that the person who claims to have signed it is indeed the signature owner and signed that specific version of the document, without edits.

It’s like a server handing a user a document that says: “I attest that user_12345 really has the app_roles: admin and editor” so they can present it to other systems that trust this authenticator.

Once we have a header and a payload, we can perform the remaining actions to generate the token: encode them in base64Url, concatenate with a dot, generate the signature with the chosen method, and concatenate that with a dot to the rest as well.

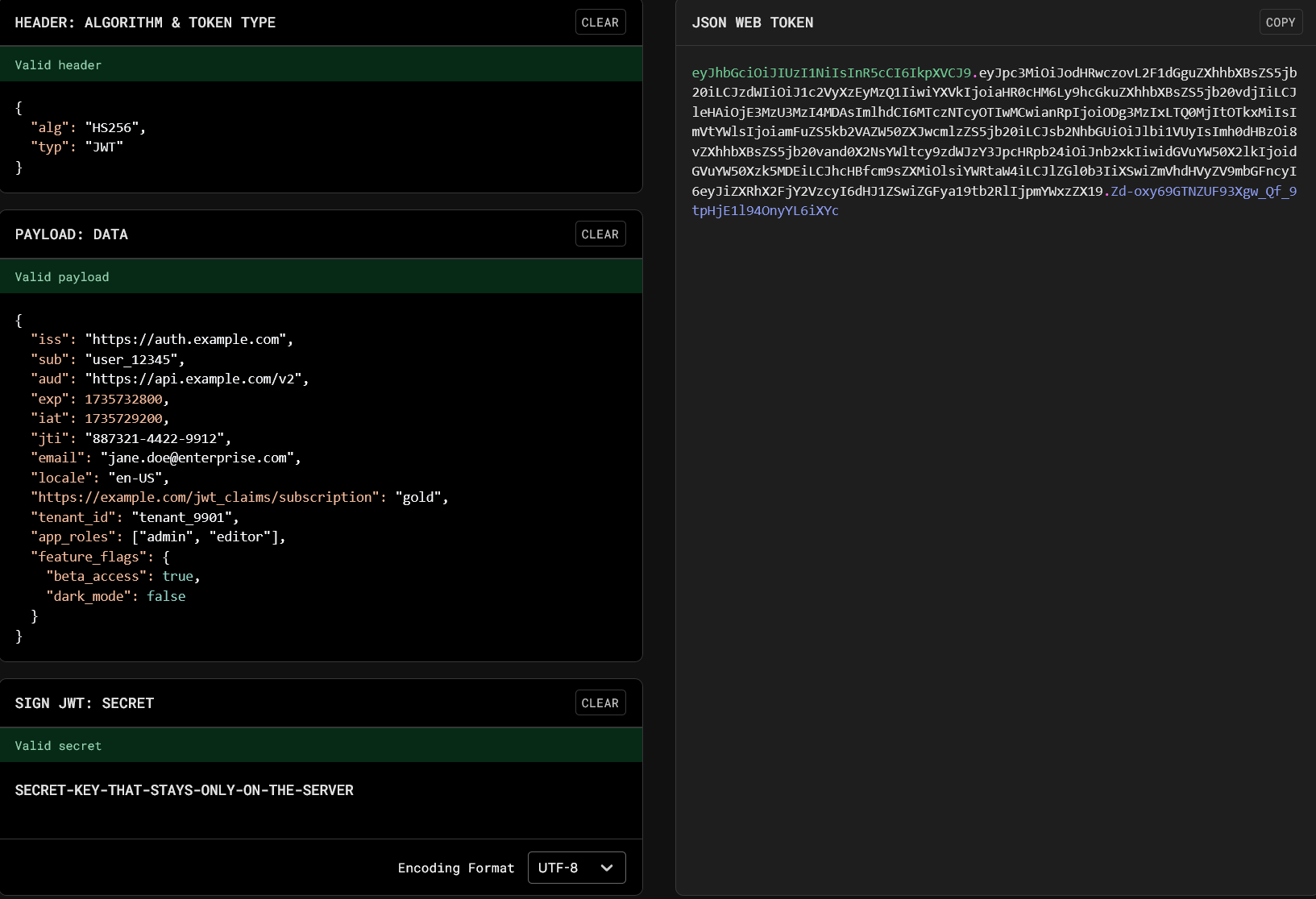

It’s easier to visualize using the jwt.io site as an example:

For the key SECRET-KEY-THAT-STAYS-ONLY-ON-THE-SERVER the HS256 algorithm was used, wich would be a good option for a monolith application or multiple services on the same machine. For distributed systems, algorithms like RSA (RS256) could be used, being verified via the server’s public key pair, decreasing the chance of the key being leaked.

This is how Google and Facebook social logins work, for instance, guaranteeing with their public keys that the tokens were signed by them.

Revocations and Renewals

A major advantage of JWT, as mentioned earlier, is being stateless and not needing database queries for authentication, but this brings a challenge. How do we know when a user’s access has changed or been revoked?

Imagine needing to ban a user immediately or change their access level. If they already have a token saved in their browser, could they keep using the systems without logging in again, using their old access indefinitely?

To solve this, 2 tokens are used in practice:

- Access Token: This is the token used in requests (with Bearer) and has a short lifespan, 15 minutes for example.

- Refresh Token: This is a long-lived token, 7 days for example, and is usually an opaque (random) code saved in the database and returned to the user securely, in HttpOnly cookies for instance. It is not accepted in requests other than the renewal itself.

Note that it is recommended to store the Refresh Token in an HttpOnly Cookie so that JavaScript code in the browser cannot read or access it. The browser itself resends it when making a request to the same domain.

Thus, the flow for the user (in practice, the client application) works as follows:

- Client logs in and receives the Access Token and the Refresh Token;

- Requests are made using the Access Token;

- Upon realizing it is close to expiration (via the exp field), the client requests a new Access Token from the server (the Refresh Token is sent automatically by the browser);

- The server checks if there have been changes and returns a new valid Access Token for the next time window.

This creates a hybrid model, where most requests are fast and stateless, reducing validation involving the database and state, while maintaining security so the user cannot keep using old permissions and access for too long.

Note that it is up to the servers to implement the function of rejecting expired JWTs.